Logistical Issues

The major obstacle to a global information environment would be logistical, as not all those accessing information will have the means to access the vast array of data that is available electronically. Of course, within the confines of the information centre the apparatus would be expected to be up to date and capable of handling large bandwidths of knowledge. Accessibility offsite, although, would not necessarily require high a specification computer terminal, but would need to be moderately up to date and more importantly internet access would be required.

A "global" information environment then will depend on the technological growth and development of countries around the world, more specifically the reach of the worldwide web; the affordability of the necessary apparatus to connect to the information superhighway; finally a level of literacy to be able to search and exploit the information that is accessed.

According the internet penetration data gathered in June 2010 by the Internet World Stats website 28% of the world population has access to the internet. Populations of only three of the world regions have more than 50% access to the internet (N. America 77%, Australia/Oceania 61% and Europe 58%). Asia where almost half of the world population reside (3.8 billion), the internet penetration is only 22%. Africa with a population of 1 billion is the region with the least internet penetration with only 11% of the population with access. These statistics show that a truly "global" information environment is a long way from now. Although the future may realise a global information environment, it will take a considerable amount of time to provide an economically acceptable solution for the developing countries to participate in the information revolution.

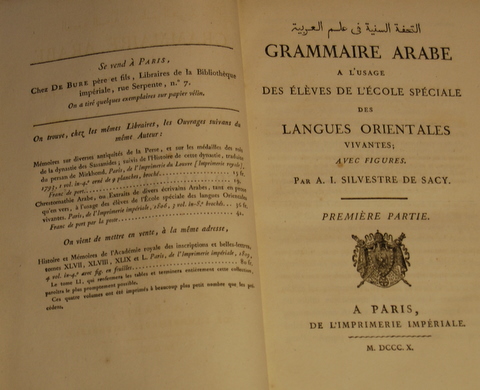

Another logistical factor is the language of global information environment. Initially, there was an issue of supporting scripts other than standard Latin script for digital systems, but when scripts had been created there were conflicts in the encoding, this meant that programmes could not display fonts or scripts unless they supported their encoding. Similarly, internet browsers could not display scripts, unless the encoding was supported by the browser. With the arrival of the Unicode standard, however, the issues are being resolved gradually. Unicode "provides a unique number to every character", regardless of platform, programme or language, thus avoiding the risk of corruption when two encodings are used for the same character (Unicode Consortium). So, a paperless information environment for the Arabic language is not very near at all. A lot of material has been digitised, but they are in PDF and are not full text searchable. Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software is available now for Arabic too, so this has enabled to expedite the digitisation efforts.

Further problems in the Arab world are of authenticity. There is suspicion amongst the Shiite and Sunnite sects that the other distorts classical texts to suite their own ideologies. Cairo is the centre for Sunnite publishing houses and Beirut for the Shiite. Printed books with similar author and titles from the middle ages are often the target of alteration. Although a lot of these classical works are now available in electronic form and are even fully searchable, they are more prone to modification than their printed counter parts. Copyrights are not easy to enforce in this region, so almost anyone can copy the whole text, make their amendments and publish online. The onus of authentication would then rely on the content providers of databases of such collections.