|

South Deccan Prehistory Project

Research Background

Project Team

Training

Publications

Media and Blogs

Protection of Sites and Monuments

Past Events

Acknowledgements New Museum

Sub Projects

Origins of Agriculture in South India

Bellary District Archaeological Project

Sanganakallu-Kupgal Project

Ashmounds of South India

(photo gallery & gazetteer)

Web Links

winnowing Cajanus cajan.

Photo by J.A. Soldevilla

|

|

The Archaeobotany

of South India and Agricultural Origins

The

origins of agriculture represents a fundamental change in

human economies that impacts social organization, demography

and perception of the landscape. In South India this is traced

toi the Southern Neolithic, which has long provided evidencefor

the earliest pastoralism in Peninsular India. The wellknownsite

category of the Southern Neolithic is the ashmound,which has

been shown to be an accumulation of animal dung at ancient

penning sites.

In

Northern and Eastern Karnataka, there are two important categories

of Neolithic sites. Permanent habitation sites, where agriculture

was practised, were often located on the peaks of granite

hills that punctuate the plains of Karnataka (see photo below).

In addition there are enigmatic 'ashmound' sies which consist

of large, heaped accumulations of burnt cattledung, the largest

some 8 meters in height and some 40 meters in diameter. Archaeological

evidence from a couple of the ashmounds indicates that they

are sites of ancient cattle penning where dung was  allowed

to accumulate and periodically burnt, perhaps in seasonal

rituals. The ashmound sites were encampemnts for the movement

of pastoral groups tied to the agricultural production at

the more permanent sites. allowed

to accumulate and periodically burnt, perhaps in seasonal

rituals. The ashmound sites were encampemnts for the movement

of pastoral groups tied to the agricultural production at

the more permanent sites.

An

important part of the research in this project has been archaeobotany

(or paleoethnobotany). Archaeobotanical sampling and analysis

has been carried out by Dorian

Fuller since 1997, and continues, including research by

students and post-doctoral colleagues. Work on the plant remains

from the hilltop village sites, or non-ashmound layers within

sites, has established that subsistence focused on the cultivation

of small millet-grasses (including browntop millet, Brachiaria

ramosa, and bristley foxtail grass, Setaria verticillata)

and pulses (mung bean, Vigna radiata, and horsegram, Macrotyloma

uniflorum). These crop species are native to Southern

India and were probably domesticated in the wider region,

although within the actual granitic landscape of the Ashmounds.While

horsegram and the millets can be found in the savannah environments

like that of the ashmounds, with wild mungbean is restricted

to moister forests such as in the Western Ghats and parts

of the Eastern Ghats. This evidence raises the likelihood

that South India was an independent centre of plant domestication

in the middle Holocene, perhaps ca. 5000 years ago (which

has been discussed in several papers by

Fuller and others). In addition there is evidence

for the use of as yet unideintified tuber foods.

During

the course of the Neolithic a number of other crops deriving

from other regions were introducted. The chronology of these

introductions is now supported by direct radiocarbon dating

of grains. Introductions include Wheat (Triticum diococcum and

free-threshing wheat) and Barley (Hordeum vulgare),

derving from the northwest, were adopted 2000-1900 BC. Somewhat

later crops of African origins, the Hyacinth Bean (Lablab

purpureus) and Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum),

by ca. 1500 BC.

Bucket flotation being carried out at Hallur

in 1998. Professor

Ravi Korisettar supervises.

From

2003-2006,

with the support of the Leverhulme Trust, research has been carried

out on the wood charcoal from Southern Neolithic sites,

principally by Dr. Eleni

Asouti. This research has required detailed background research

in wood

anatomy and vegetation ecology, as well as ethnobotany will

will soon be available in a the book Trees and Woodlands of

South India: An Archaeological Perspective by Eleni Asouti

and Dorian Q Fuller, published by Left

Coast Press, and in India by

Munshiram Manoharlal.

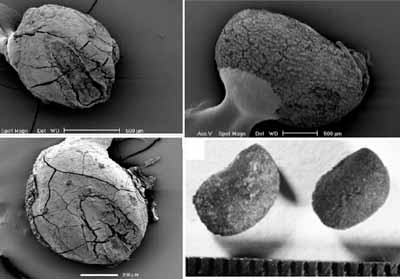

Archaeological

examples of the most common seeds on Southern Neolithic sites,

clockwise from top left: Brachiaria ramosa, Vigna radiata,

Macrotyloma uniflorum, Setaria verticillata. Archaeological

examples of the most common seeds on Southern Neolithic sites,

clockwise from top left: Brachiaria ramosa, Vigna radiata,

Macrotyloma uniflorum, Setaria verticillata.

Other important evidence

includes wood charcoal that suggests the beginnings of tree

cultivation towards the end of the Neolithic, 1400-1300 BC,

including Citrus (probably the citron), and mangos.

Charcoal from sandalwood testifies to the beginnings of trade

in this important aromatic timber, which has long been important

in South India, although it may have been introduced originally

from Indonesia. In addition seed findes of the bengal madder

(Rubia cordifolia) suggest exploitation of plants for

dyes, which may be linked the the emergence of textile production

after 1700 BC, but esepcially in the later Second Millennium

BC. This is indicated by finds of spindle whorls, while charred

seeds of cotton and flax have been found at the site of Hallur

from 1000-900 BC.

(For further information,

see thre publications by Fuller or Asouti: goto

references). also: earlier

webpages on this research.

|

|

.jpg)

.jpg)