1920s Diary

The woman rollerskating on the right wrote this diary

Wednesday evening, 13th June

I am only just beginning to write this, as I haven’t been able to settle down to anything, but I have made brief shorthand notes every day.

To go back to the Sunday when you said goodbye, when I was half-way downstairs I wanted to go back and kiss you. I wonder if you were trying to show by holding me close, that you would not mind my kissing you? Anyway, my reactions are not quick enough, and although I often want to kiss you when away from you, when you are there the chilling detached atmosphere surrounding an analyst is too strong. Also one of the first things that occurred to me afterwards was your telling me a simple gift could not be accepted, and I think that and your after-holiday letter are still affecting me. It seems that my interest in you and thought for you were thrown back unwanted, and now it is difficult to believe in any advances implied by you.

During the week I had several waves of apprehensive panic, and when in the train on Friday morning felt afraid for about a minute of the long lonely day ahead; but the journey passed off all right. When passing Dartmoor it reminded me of the old days when I used to go tramping there with Father, and I had a little weep, being alone in the carriage. (Since then I’ve often wished he were here, or I could write to him, because he was interested in this sort of country, and we shared its pleasures.)

When I arrived at Liskeard that Friday evening there was a soft Cornish rain. Nell met me with a farm motor van and we rattled quickly to her cottage. It was strange to see bluebells and violets still in flower along the hedgerows, thanks to the wonderful climate. I slept the night through without dreams.

_______________________________________

Saturday 9th June

After breakfast unpacked my things, and then we went for a short walk towards the moors, but it was too misty to see much.

In the afternoon Nell and I went to the Searles’ farm, an unexpected pleasure, because Mrs S. - who has become a great friend of hers during the last year - is very shy, and had begged her not to take me there. So I was left sitting on a stile in the next field, but when she heard of this her hospitality conquered her fear, and I was called in. Fortunately she liked me, and her little son of 18 months also took a great fancy to me, so all was well. We stayed to tea, and afterwards saw the fowls fed and the cows milked. By this time I was very tired and was extremely grateful for a glass of milk warm from the cow. I felt very weary and out of touch with life, unable to enter into the life of these good people, although I seemed to on the surface.

In the night I was awake for an hour or two, and dipped into Methuen’s "Anthology of Modern Verse", but everything seemed so sad that I was overwhelmed by "the heartbreak in the heart of things", feeling it was impossible to be really jolly and cheerful. Then, thinking of an incident in which I was rude to Father, I realized that if he had been able to love me I don’t think I should have been unkind, and this made me feel that one should give love whether it seems wanted or necessary - assuming one can express love.

Sunday 10th

Nell brought me a cup of tea in bed; and then my "cloud" of depression descended upon me, a trouble that I have had from time to time since I was 14; but before my breakdown I could always see the light at the end of the tunnel, whereas since I am in mortal fear of the horror of repeated collapse and chaos. During the morning I gathered flowers and arranged them, and went for a short walk alone. At the midday meal I had a terrible panic, and felt my whole stay would be a purgatory, and the journey home a hell. Thank heaven, it only lasted about 10 minutes; such a feeling would soon drive one mad.

In the afternoon we were all very sleepy, and slept till past 5 o’clock. In the evening we went to the farm, and dear little Mrs Searle gave us fresh milk and junket and cream. I was very tired, too weary to go and see the cows milked.

Monday 11th

At 8.30 I walked to school with Nell (1½ miles) and back by myself. Then made my bed, and tried the piano, which is execrable for playing, but may serve for practice. Wrote two letters. In the afternoon I walked to the pillarbox to post them, and back a different way - about a mile in all. To the farm again in the evening, but very tired and lethargic, absolutely no interest in details.

Tuesday 12th

Woke feeling very unwell, but struggled to get up and go to school with Nell. Spent several hours in the morning trying to write a short lipreading advertisement for the B.M.A. handbook with absolutely no result. In the afternoon I did put a few sentences together. About 4 o’clock I went alone to the farm to get some cream, and Mrs Searle kept me to tea. Later Nell arrived, and we all went in Mr S’s motor van to buy some pigs. It is a Ford, and part of the way was over rough fields. Sometimes I got out to open gates, and I think this and the jolting did me good, as I felt fresher afterwards.

Wednesday 13th

[Dreamed about Mrs Chalmers in the night.] Got up about 9. Walked to St Cleer (about 1½ miles) to buy postcards - a fine driving rain all the time. Had a fit of panic on receiving a letter in reply to mine to a friend in Bodmin about going to spend a day with her. (Although only 14 miles away it means a 3½ mile walk and 40 minutes train journey.) Wrote some letters and managed to send off a short lipreading advertisement, but very "funky" about it as I’ve absolutely no judgement just now. After lunch went to post and part of the way to meet Nell. Sat in garden in evening writing diary.

In course of conversation, Nell’s mother said she had found nothing was ever so bad in reality as one imagined it would be, which echoed one of your statements. When going ro bed she thanked me for my kisses.

Thursday 14th

Made my bed, cut some lunch ready for the day’s outing, wrote some postcards, and packed up some flowers for Miss Collins. At midday the Searles arrived with the motor van, and I spent the day with them, scouring the country for eggs, butter and cream ready for the Saturday market at Plymouth and I did not reach home again till 8 o’clock. It was a delightful day; several times I became desperately tired but once a timely rest by the wayside, and again tea in Liskeard revived me, and I arrived home feeling fresh and fairly ready for my solitary trip to Bodmin the next day. Mrs Searle seems to like me very much and kissed me when I left her.

Friday 15th

During the night when awake my mind revered to the journey to Bodmin, and I fantasied a tramp or gipsy overpowering me and committing rape, and felt there would be element of pleasure in the experience for me, and from this vaguely sensed some possible connection between panic and sex.

It was a misty morning, with more than a hint of coming rain, but I wanted to get the ordeal over, so I started off on the lonely 3½ mile walk. Almost immediately I had a panic, and for five or ten minutes I was breathless with fear at being alone in new surroundings, and at the prospect of the effort of talking and appearing natural to my friends. This passed off, and I enjoyed getting into the swing of the hilly walk, except for a tiny quiver at meeting two horses loose on the road, as one of them stopped to look at me in a way I didn’t like, but I suppose in reality he was nervous of me. I spent 5 hours at Bodmin, and on the whole enjoyed talking of old times and picking up the threads of our slight friendship. But several times

tears came to my eyes because the dear old Cornish woman reminded me of the holidays I had spent in her house with Father, and I imagined him looking on from the other world. When having tea, before leaving, I had another panic which passed off before I said good-bye. After the 40-minutes train journey I finished off my letter to Miss Collins at Doublebois station, and walked the 3½ miles again in a fine driving rain. I was healthily tired and slept from 10 to 7.30, having dreams that I have written elsewhere.

Saturday 16th

During the morning I had an interesting little talk with Nell’s mother about sex and birth. Then prepared to go and join Nell at the farm, as she had slept there to help them early this morning when leaving for a day at Plymouth market. We spent the day there together, doing what we could in the way of washing-up, getting water from the stream and fetching bread from the village. We also tried sketching one of the dogs. Returned home about 10.

Mrs Searle (at the farm) now hugs and kisses me. I think she thinks I respond, but I very seldom do really. I feel awkward, self-conscious and unable to understand love.

Sunday 17th

Slept well all night. Breakfast at 9. Spent a short morning drafting letter to my mother about N. and psycho-analysis. Had early lunch, and started off with Nell to walk over the moors to Cheesewring Tor. I think today for the first time I had a little spontaneous energy, but as usual I got very tired on the way back from the tor where we had a very extensive view of Devon and Cornwall – though it was not a long walk. We went to the Searles to tea, and spent the evening there.

Monday 18th

Before getting up I was thinking about my fear of a motor going backwards when I am in it, especially if it is left standing on or near an incline, and I got a vague half-remembrance of the days when Father used to take me over Portadown Hill in my pram, probably because Mother has told me he would let it run down the hill (with me in it) and then run fast to catch it up. If this is an explanation of my fear, I wonder if the mere remembrance cures it, or whether I have to use will power to remember the explanation every time I get the fear?

I spent the morning writing my long letter to my mother. After lunch, Nell’s mother and I went up the road to meet Mr Searle with the van to go a long drive to various places where he does business. While waiting for him I noticed a wagtail go into a hole in a stone wall and out again, and on going to investigate found, as I hoped, a nest with three little ones in it. We got home again about 5, had tea, and I played Halma with Nell’s mother, after which we talked and read, and so to bed.

Tuesday 19th

Between 9 and 12 did various little household duties, wrote 18 picture postcards, and tied up magazines for my brother. After lunch walked to St Cleer (1½ miles) to post the cards and magazines; saw the ancient St Cleer Well there. On the way back peeped at my wagtails’ nest, and climbed into a field to see the remains of two ancient crosses known as "King Doniert’s Stone". I don’t like these solitary walks between high hedges, as my mind quickly reverts to analysis, and goes round and round the question, - I rage against you. In a letter Mrs Inman says she hopes my ideas will allow themselves to be readjusted during my holiday, but I can’t marshal many ideas. There doesn’t seem much wrong with the ideas of working hard, thinking for people and doing things for them, and if it is all uninspired by feeling, I can’t manufacture feeling, so I must go on "acting". I just feel hopeless and helpless, and you are unhelpful, so I suppose I can but wait for something to happen in the unconscious.

I returned home and tried to sketch the house from the garden in pastels. Then walked part of the way to school to meet Nell. After tea, did a little embroidery, and Nell showed me the postcards of her German trip last year, which revived my desire for travel. Went to the Searles for cream, butter and eggs. After supper finished reading Maude Royden’s "Sex and Common Sense".

Wednesday 20th

A very wakeful night, but perhaps due to the time of the month. Had panicky feelings about spending a long day in the van alone with Mr Searle on Thursday, but decided to take knitting, a book and writing materials for the wayside rests while he climbs to the farms for their produce. Then my mind reverted to the disappointment of analysis, and I tired myself out trying to see a way out, but everything is blank, and I could only cry violently over it all.

Had breakfast at 7.30, and walked to school with Nell to bring back a geranium in a pot which had been taken there for the children to draw. A cold, blustery day, and I was tired out when I got back. Read the newspaper, made my bed and practised a little at the piano. After lunch wrote up my diary, and then went alone to the farm as I had promised to help to wash eggs. This perhaps needs explanation. Mr S goes to outlying farms and buys eggs, butter and cream which he sells at Plymouth market. At some farms the eggs have the dirt and stains wiped off each day as they are gathered; at others they are packed up as they are. It is the latter which need washing to make them look nice for market. I spent two hours at this, then had tea with them and returned home. Then I had an enjoyable peaceful hour sitting in the garden in the golden sunshine, writing and reading, while Nell sang some sweet songs, so that for a time I felt almost happy. Did a little embroidery after supper.

Thursday 21st

Packed up some flowers to post to a friend, cut my lunch, and started off at 10.30 with Mr S in the van. Had a busy time helping to pack eggs and butter as he brought them from the various farms, and while he was away on these errands I tried to write a description of "negating". Returned home with him about 3.30, had tea there, and then started off again to Liskeard (4 miles) taking with us this time his wife and baby, mother-in-law and brother-in-law. Arriving there, we scattered on our own business; I posted my package and did shopping for Nell. I reached home between 6 and 7, had supper, did some embroidery and finished reading "The New Children".

Friday 22 June

Slept well all night, having some dreams which unfortunately I cannot remember. Had breadfast in bed, and re-read my old favourite "The Great Stone Face". Spent the morning in taking a little package to the farm for Nell. After lunch finished writing diary and letter for Miss Collins and went to post these. Then Mrs Hathill and I walked about a mile and a half to Tregarrick, a charming old farmhouse on the moors, where Mrs Searle’s parents live. We had been invited to tea and received a great welcome. Nell came there straight from school. We were shown all the farm animals and birds, and were taken to a bungalow used in the hunting season by some wealthy people who live in Devonshire, but at other times empty and looked after by the people at the farm. It amused me to imagine what the owners were like, judging from the pictures, books and furniture, etc. We arrived home in time for bed. This was a fine day, the first time I had been able to wear a summer frock.

Saturday 23rd June

Slept well but had several anxiety dreams, and woke with the shaky abdominal feeling of fear. Very tired, and did not have breakfast until 9. Nell and I started out soon afterwards to visit two very isolated moor farms in order to collect the quarterly subscriptions towards the expenses of the district nurse. It was a gloriously sunny day with a cool breeze. We found it necessary to look out for adders as we nearly stepped on one in a sunny coomb. Tregarrick lay on our way and we were invited in and received with typical Cornish hospitality - a glass of milk and cake spread with clotted cream. Then we went on over the moors, had a picnic lunch, visited the two farms, and returned to Mrs Searle’s to tea. I read Maeterlinck’s essay on "Sincerity" while the others were attending to the cows and poultry. We returned home about 7, laden with chicken and cabbage for the Sunday dinner, a can of milk, a "broody" hen and other impedimenta. Did some embroidery in the evening and went to bed tired and sunburned.

Sunday 24th

Slept well all night (with dreams which I have written elsewhere) but still drowsy in the morning. Had breakfast in bed. The morning passed quickly doing various little things – making bed, gathering and arranging flowers, tacking a jumper for Nell and copying extracts into my commonplace book. After lunch we all rested in our bedrooms, and I cried over Thomas Hardy’s "Afterwards" because it reminded me of Father’s love of nature. After tea, Nell, her mother and I went for a walk of two miles or more to some beautiful beech woods by the Fowey river. I was very bored and restless, and utterly failed to feel the extreme beauty of the scene though I realised it mentally. After supper we had a long talk – reminiscences of the old suffrage days, which did Nell and her mother good, I think, after 4 years of this isolation.

Monday 25th

A wakeful night, with much puzzled thinking, but I can see no way out without some sort of revelation. Nell brought me a cup of tea and I tried to sleep, but could not; very unhappy. Possibly I am beginning to worry about the homeward journey; I wish I were safely back. During the morning I used Nell’s bicycle for the first time, as the damp, windy weather and other engagements had usually kept me from doing so previously. I had my first experience of running down a gentle hill, which made me feel I had made a tiny step forward. In the afternoon I wrote postcards and a letter and walked to the village to post them. After tea Nell and I went to the farm and I enjoyed playing with the baby. It is nice when a child grasps you by the hand and leads you away to a field to play, as he knows nothing of adult "politeness" and you feel he really wants you. Today I had a vague realization of the necessity of doing all one can, and on one’s own responsibility, but only a glimpse, not a conviction.

Tuesday 26th

Slept well all night. Too misty and showery to go cycling as I had hoped, so spent morning writing out extracts, etc. I was delighted to come across Olive Schreiner’s "Dreams", a collection of little allegories - one of them seemed so symbolical of psycho-analysis. After lunch it cleared up, so I went for a short cycle ride. It is disappointing that I still have so little confidence that I sometimes "foozle" mounting, even when there is no one in sight. Then I sat in the garden writing a letter. After tea Nell and I went for a 2 or 3 mile walk to see a cromlech called Trevetly Stones.

Wednesday 27th

A very fine day, so I felt I ought to get out on the moors and try to do some sketching. I hated being alone, and didn’t like going through the farmyard where there were some cows and a bull, but I enjoyed sitting at the top of a tor, and managed to do a small sketch. Very tired after this, and wanted to go to sleep after lunch, but I had promised the Searles to go and wash eggs. When I arrived, however, there were very few to be done, as they had re-arranged their work, and instead we went in the van to collect cream, and returned at high speed to catch the postman at the cross roads. I had tea with the Searles, and Nell came up during the evening. We returned earlier than usual so that I could do my packing.

Thursday 28th June

Did not sleep well, and very "panicky" about everything before I got up. There were the discomforts I have usually had (since my breakdown) - no appetite, slight diarrhoea, general shakiness and restlessness and fear. Soon after 9.30 the van arrived with Mr and Mrs S. and baby. We went to the first farm on his round (his father-in-law’s) to get their eggs, and by the time these were packed properly the time was running short, so that speed limits were ignored in order to get me to Liskeard station in time. This excitement probably helped to keep off panics, but it also tired me and gave me a nasty headache for most of the journey, so that I could not do any writing as I had hoped. Norah met me at Fratton and we arrived home about 7, my "holiday" over. Miss Collins’ letter was awaiting me, with the disappointing news of further delay, and the old atmosphere of hopelessness closed in around me as I realized that the same dreary meaningless round lay before me, everything turned to "Dead Sea fruit" through lack of feeling, love, or interest - in the fourteenth month from the beginning of analysis!

_____________________________________________

Thursday 26th July

I don’t know whether I got rid of a good deal of emotion at analysis this evening through hating Miss Collins but I left feeling decidedly freer, in fact quite glad at the prospect of being relased for five weeks from the annoyance of floundering about in endless, unilluminating associations, and with a feeling that I could forget that annoyance and so throw myself whole-heartedly into work and pleasure during that five (or rather, six) weeks.

Friday 27th

Went to Winchester, enjoyed the last lesson and tea with my pupil, and another tea with an old pupil and his wife who sent me home laden with lavender and carnations. Had a half-panic in the train, and unfortunately as usual felt too frightened to think of making associations. But on the whole felt freer, happier and more confident all day. In bed, for the third night in succession had extremely vivid erotic fantasies, bringing physical desire in their train, so I turned to reading and finished Barbara Low’s book of which I had previously read only two chapters. This meant superficial reading, but as I already have a rough idea of psycho-analysis I aimed chiefly at new and arresting points with the idea of a slower re-reading later on. It has certainly helped me on many points, such as dream interpretations and the nature of transference. It also seems to explain the slowness of results in my case, for I appear to have "talked over" far more than "reliving emotion".

Saturday 28th

Busy at home in the morning, also shopping, then - at 1.15 - with the L. and P. [Literary and Philosophical Society] to Chichester and Bosham, a very interesting trip. At times I felt very unwell and my legs ached horribly, probably owing to the onset of the delayed period; but I reached home feeling fresh and cheerful about 10pm.

Sunday 29th

A pleasant day, as my dearest ex-Waac [Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps] friend arrived unexpectedly at midday having come from Surrey by char-à-banc and two nice girl friends of Norah’s came to tea.

In the morning I was doing some dyeing for Mother, and found the greatest difficulty in concentrating my attention upon the details. In the evening I was very tired and "achey", but doubtless the period was responsible for that.

Monday 30th

Spent first part of morning at housework, then went out on business for a friend. In the afternoon Mother, Norah and I went to a cinema to see the film of some of the B.M.A. [British Medical Association] functions, and there were two other films showing some really humorous incidents which gave us some hearty laughs. In the evening I gave a lipreading lesson. During the day I had several spells of feeling ill and tired but there is no doubt that the period this time is much more profuse and troublesome.

Tuesday 31st

My morning was rather put out of joint owing to the non-arrival of my music-master, but I made use of the time to straighten some papers. Shopping in the afternoon, fairly good piano practice after tea, and then visiting some friends with Mother. During the day there were slight attacks of discontent, and rehearsals of imaginary disagreements with Miss Collins.

Wednesday 1st Aug.

Very busy all day with housework, shopping and preparing the sitting room for the sweep. I also tore up a lot of old photographs in an attempt to keep to my determination to get rid of something, however small, every day in the hope of making progress in the Herculean task of clearing away rubbish and keeping only what is useful and beautiful. Have felt very energetic and have not bothered about analysis.

Thursday 2nd Aug.

I was occupied most of the day "spring-cleaning" the sitting room, doing the ceiling, walls, paint and carpet. A few slight attacks of discontent about analysis.

Friday 3rd Aug.

I slept till nearly nine o’clock, probably because of a bad night owing to erotic fantasies and desire; only two more nights before I can gain some relief in that respect. A busy day, spring-cleaning stairs, finishing the sitting room, gardening, practising piano, etc. But most of the time life seemed to be lived under a leaden weight, making everything a treadmill rather than a form of expression.

Saturday 4th Aug.

I got up at 7.30 intending to go cycling, though very unwillingly as I felt dreadfully nervous; but as Mother had an attack of lumbago, probably due to using vacuum cleaner, I gave up the idea and gave her breakfast in bed. Norah was also in bed owing to period, so I had to take her light meals during the day. I felt very depressed and unwell early in the day, and overpoweringly drowsy in the afternoon, so that I slept two hours and was still tired on waking. I was better after tea, practised music fairly well, and went to open-air fête with Mother where I won a rifle shooting competition, not a great achievement but it helped to restore some self-respect. Late in the evening had a pleasant walk to see Eugenie and ask her to tea on Monday.

Sunday 5th Aug.

Got up soon after 7, went cycling, gave Mother and Norah breakfast in bed. Beginning to worry about Mother, as her lumbago is worse and I get morbid fears that it might be something more serious. I went to hear the Welsh Gleemen on South Parade Pier in afternoon but was disappointed in them. Gardening, and writing a long letter to Canada in evening.

Monday 6th Aug.

Mother called me from her room about 6am as she had hardly slept all night because of the pain of the lumbago. I helped her to move, gave her a cup of tea, and then went back to bed for a little while. I was busy at home all day, as Mother didn’t get up. Eugenie came to tea and stayed most of the evening. I had horrible waves of hopelessness, morbid fears about Mother’s illness, feelings of utter inability to tackle life, especially as Mrs Hattrill is coming to stay with us soon; fortunately these did not last long - normal life would be impossible if they did.

Tuesday 7th Aug.

Mother in bed all day (though she seems a little better) so I have had a good deal to do, as I also had a music lesson in morning, gave a lipreading lesson in the evening, and went to fetch a little parcel from a friend of Mother’s at Fratton. Felt very tired at various times during the day, and so often felt unready for everything.

Wednesday 8th Aug.

A very tiring day. Mother still in bed, and though better she is still weak. I went to meet Mrs Hattrill at midday. It is appalling to find how the slightest departure from my usual leisurely life "knocks me out" at once and it seems to prove my contention that any "improvement" due to analysis is very illusory. I get terrible waves of physical exhaustion where every nerve seems exposed, and the strain of planning and deciding all the little household tasks is a monstrous burden - and this in spite of the fact that I really want to do everthing that is necessary, and any normal person would do it with ease.

Thursday 9th

A terrible morning; I woke up feeling a mass of nerves, and was on the verge of a physical collapse all the morning, but I just managed to do the bare essentials. Mother in bed all day, but rather better. In the afternoon I lay down and had a good cry, which probably eased me as I felt better in the evening and was able to carry out an engagement to go to see "H.M.S. Pinafore" with Eugenie without undue fatigue.

Friday 10 Aug.

Much better today. Woke up feeling fairly normal after a good night’s sleep. Shopping in morning after house-work, had a sleep in afternoon, went to library for Norah in evening, also gardening, reading, etc. Mother up most of the day - much better.

Saturday 11th

Slept well. Gave Mother breadfast in bed. Housework and shopping in morning, slept in afternoon, music, gardening and reading in evening, also a visitor called. Fairly cheerful and energetic most of the day.

Sunday 12th Aug.

I went for a short cycle ride at 7.30 but it made me very exhausted and faint - in fact, I felt unwell and on verge of physical collapse all day. I was busy in the house in the morning, slept in the afternoon, and had two friends to tea who stayed most of the evening. In the morning I had a nasty fit of rebellion and disappointment about analysis.

Monday 13th

Felt very unwell on waking, and most of the morning, and had one of my "consumption" scares in consequence. Shopping and letter writing in morning, to Cosham with Mrs Hattrill in afternoon to see friends, and gave a lipreading lesson in the evening. On the whole I think I felt better when bedtime came.

Tuesday 14th

After breakfast Mrs Hattrill suggested spending the day at Emsworth, her native place, so she and I started off by the 11.25 bus, had a light lunch on arrival, then explored the millpond and shores of the harbour to a running commentary of her reminiscences. In the afternoon we called on friends of hers, a most interesting family who entertained us to tea; this interlude (with its opportunity for character study) I enjoyed, but most of the day I felt colourless and desolate, utterly unable to take real interest in anything, though as usual I pretended to for Mrs Hattrill’s sake. To bed tired and depressed.

Wednesday 15 Aug.

Very tired most of the day because I was awake for more than 3 hours in the night and cried bitterly from a sense of isolation, the cold aloofness of the analyst, the dreariness of doing things for other people without any feeling, and the treadmill of work without interest, though I was told months ago work would bring understanding. Housework and shopping in morning, writing letters and diary in afternoon, music and gardening in evening.

Thursday 16th

I was awake in the night and cried from sheer hopelessness. This led to sleeping late in the morning and feeling very unfit. Busy in the house in morning, and also made a macaroni-cheese for lunch. Had hair cut and shampooed in afternoon. Wrote letters and had good piano practice in evening. Saw some nice verses in the newspaper called "Take Heart and Begin Again" which made me feel I ought to make the most of each day as it comes without dwelling too much on the past.

Friday 17th

After crying a little I slept well all night, but did not wake till past 8. Busy at home in morning. Began re-reading Freud in afternoon (in order to make a summary of the book) - this started me crying again. To library with Norah in evening, then paid a call with Mrs. Hattrill. Felt fairly energetic and happy.

Saturday 18th

Slept well, and yet extremely weary when I woke. Cleaned a room and wahed some handkerchiefs in morning. Continued summary of Freud in afternoon. Visiting friends with Mrs. Hattrill in evening, but could not be really interested.

Sunday 19th

Slept well after some hopeless crying. Busy in the house in morning; tried to grapple with Freud in afternoon but could not concentrate, indeed I was depressed and without intiative all day. Gardening and writing in evening, also a little stroll with Mother just before bed.

Monday 20th

I went to the station to see Mrs. Hattrill off by the 9.50, and spent the rest of the morning and afternoon cleaning and re-arranging my bedroom which I must give up to-morrow to my friend L. After tea, piano-practice, then gave a lip-reading lesson. Norah had a fit of nerves and expected me as usual to hear her woes and reminiscences. People take it for granted that I am at their service, but I have nobody to go to in my almost continuous depression.

Tuesday 21st

A wakeful night with some crying. I had an awful wave of mental horror at breakfast; it only lasted a minute, but the horror is indescribable. Had a music lesson, and was busy afterwards getting things ready for L. who arrived about 2 o’clock. Another friend over from Bognor for the day also came in to tea unexpectedly. I did nothing worth mentioning in the evening for I felt worn out. I cannot describe my extreme lassitude - no energy, mental or physical, no interest in anything.

Wednesday 22nd

Did not sleep well, felt unwell on waking and cried with a sense of forlornness. Housework and shopping in morning, slept in afternoon; felt better after tea - did some ironing, practising and embroidery.

Thursday 23rd

A bad night, awake from 3 to 6.30, but in spite of this felt fairly well all day. Took L. to the Dickens Museum in morning; slept in afternoon; needlework most of the evening.

Friday 24th

Slept well, or, rather, heavily, but did not feel refreshed - perhaps this was due to the thunderstorm which came in the afternoon. Went out with L. in morning to Museum and St Thomas’s Church; slept in afternoon. With L. on the Esplanade in evening. Not a bad day mentally, but quite incapable of any physical effort.

Saturday 25th

Slept well and seemed rather better physically in morning. Busy with light housework, then after an early lunch L. and I went by tram to Portsdown Hill. I had nervous tremors about leaving home. We were home again by 4.30, and although we had only walked about 2 miles I was very tired. Could not do anything but needlework in evening.

Sunday 26th

Busy in house in the morning. After an early lunch L. and I went and sat for some time overlooking the Harbour. Had a short read and rest before tea, afterwards L. and Norah and I played some amusing guessing games, but I had not felt well all day and by evening felt as ill as one can be without absolutely breaking down.

Monday 27th

Slept well, and have felt slightly better all day, probably because the period has really commenced. I was busy in the house in morning; after lunch I went to Harbour station to see Eugenie off to London; had a little rest before tea, gave a lipreading lesson afterwards and practised piano.

Tuesday 28th

Very tired, consequently rather late in getting up. Had music lesson, but did not profit much by it owing to mind-wandering. After an early lunch Mother, L. and I went to see friends at Porchester, had tea with them and saw the Castle. Extremely nervy and tired by the time we returned by the 8.3 train. People must have good nerves to be able to stand so much talking and the clatter of 4 children.

Wednesday 29th

Cleaned sitting-room in morning and went shopping; rested in afternoon; went for a walk with L. in evening, and to bed early, very tired.

Thursday 30th

Slept well from midnight, and felt better physically, though still lethargic. Out with L. in morning; tried to get on with Freud summary in afternoon; did embroidery in evening. Despondent about analysis, and painfully conscious of lack of initiative and inability to love.

Friday 31st

Slept all night, but dreadfully lethargic until after breakfast, after which not quite so tired as on most days recently. Fairly busy all day, housework, shopping, friends to tea, out to the library with L.

Saturday 1st Sept.

For a change I was awake and ready to get up just before 8 o’clock. Busy at home in morning. Mother, L. and I went on L. & P. [Literary and Philosophical Society] excursion to Farlington Waterworks, taking a picnic tea. Enjoyed it fairly well.

Sunday 2nd

Awake from 4 to 6, cried a little, and very tired when getting-up time came. Out with L. in morning and evening. Rested in afternoon, feeling absolutely exhausted after lunch, and had the same feeling again just before going to bed. Horrible forebodings that I have consumption or pleurisy.

Monday 3rd

Felt rather better physically all day. Went over the Dockyard and Victory with L., a tiring expedition of 2 ¼ hours. Visitors called in afternoon. Round the Castle with L. after tea, and gave a lipreading lesson in evening.

Tuesday 4th

Felt fairly well all day. Housework and some visitors in the morning. Slept in afternoon. After tea wrote up diary, and then L. and I went to see "R.U.R." It was very horrible and made me feel very frightened.

Wednesday 5th

Slept badly, probably owing to the strain of "R.U.R." Out with L. in morning; reading at first in afternoon and then slept heavily for half an hour before tea, after which I was much better. Mother, L. and I went out to Milton and sat on the shore of Langstone Harbour; it was a delightful evening, and I enjoyed the novelty of watching the boating. I made porridge for supper on our return. According to arrangement I expected to hear from Miss Collins by this day, but have not done so.

Thursday 6th

Rather wakeful after 5 o’clock with a little crying. Very tired on waking. In morning Mother and I went over a house that is for sale; much as I should like to buy it, I am not in a fit state to undertake the responsibility , especially with no signs of improvement. Slept in afternoon. In evening Mother, L. and I crossed the harbour and sat by Haslar Creek for a time. No news from Miss Collins.

Friday 7th

After usual household duties L. and I went by 11.40 bus to Bedhampton, had a picnic lunch, looked for blackberries (not very successfully) and arrived home again about 3.30 - quite a pleasant little excursion. Nothing much happened after tea, except that friends called. Still no news from Miss Collins.

Saturday 8th

Slept well, and woke earlier than usual, but didn’t have courage to go cycling. Out with L. in morning. In afternoon I went with her to Hayling, taking tea with us, and had a delightful time paddling and sketching. On reaching home again in evening I found a disappointing letter from Miss Collins, calmly announcing another two or three weeks’ delay, after leaving me in uncertainty since Wednesday. Although she is in Southsea, and I have been cut adrift for six weeks, she did not trouble to find out how I was or to give me an opportunity of an interview, but decided off-hand that it would not be useful to see me until we can resume an uninterrupted course. After revealing her real indifference by this action she tries to assure me she would be very glad to hear how things are with me! Such an empty enquiry calls for no reply.

Sunday 9th

A wretched night of sleepless misery over the new delay and the hopeless outlook. L. and I crossed the harbour, took char-à-banc to Lea and walked to Hillhead where we basked in the sun all day, arriving home again about 7 o’clock.

Monday 10th

Slept fairly well. Saw L. off by 10 o’clock train and spent rest of morning in housework. Rested in afternoon. Visiting friends in the evening.

Tuesday 11th

Mother and I caught the 9.5 train to Droxford to visit friends, arriving home again about 7 o’clock. I was very tired, and it was a great effort to talk to people - I was, in fact, bored. Wrote to my brother after supper.

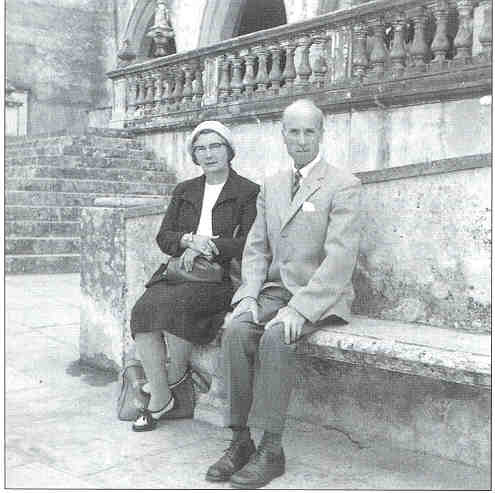

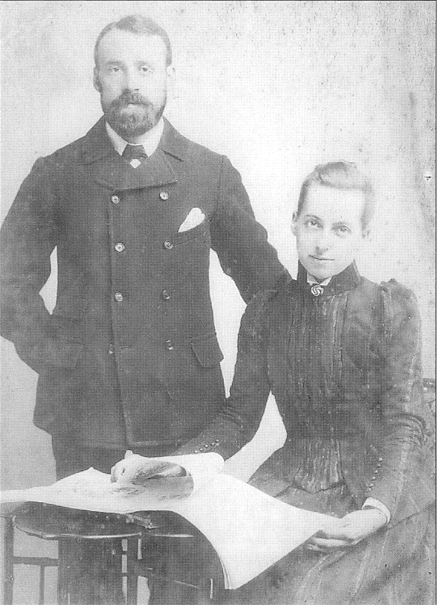

This is a picture of her brother with his wife, Norah, taken later in their lives

Wed. 12th

Very busy all day cleaning and re-arranging my bedroom so that I can sleep there again after L. having it for 3 weeks. Called on friends in evening, and had a late stroll with Mother just before bed. Not much time to think about the puzzle of analysis but still very unhappy underneath all this superficial activity.

Thursday 13th

Busy all the morning cleaning the little sitting-room which had to serve as my bedroom while L. was here; heart-breaking work because there is so much unnecessary labour and no satisfaction in the result. Rested in afternoon. Visited friends in evening and enjoyed a game of clock golf.

Friday 14th

Very busy with housework all the morning; lying down reading in afternoon; after tea, music practice, and the L. & P. [Literary and Philosophical Society] lecture where I was rather panicky at times.

Saturday 15th

A very good day. Woke early and ready to get up. Light housework in morning - also two callers. From 2.30 to 8 with the French Club excursion to South Hasting which was very enjoyable.

Sunday 16th

While awake towards morning I had a flash of insight that it is wrong for me to be disagreeable to Norah however wrong she may be in her selfish disregard of my troubles, and that one should always be kind to others. The extra hour consequent upon the change from "Summer time" enabled me to wake in good time, and I went cycling, and did fairly well considering the long period that has elapsed without practice. Busy in morning doing "odd jobs"; tried to do a little at the Freud summary in the afternoon. I became very tired suddenly in the evening, and made an awful hash of trying to write lipreading advertisements.

Monday 17th

Woke early and went for a short cycle ride. Housework and shopping in morning. Rested a little in afternoon before visitors came to tea and stayed till 7. Then Norah and I went to South Parade Pier to see "The Co-optimists".

Tuesday 18th

Woke early, but too windy to go cycling. Busy at home in morning. Letter-writing in afternoon, including advertisements for pupils whom I am half afraid to get. Visitors in evening.

Wednesday 19th

A good day. Up fairly early,busy at home in morning, out in afternoon on business to post office and station. Letter writing and a visitor in evening.

Thursday 20th

Still tired when I worke at 8 o’clock. A wretched day of mind-wandering and lack of concentration so that I seem to have done nothing of note. Had a nasty wave of fear when I saw my advert in the newspaper.

Friday 21st

Sleepless night, and felt tired and unwell all day, perhaps because period is overdue. Turning out rubbish with Mother in morning, slept in afternoon; to L. & P. [Literary and Philosophical Society] Art lecture in evening, but could not grasp all of it, and consequently felt rather bored at times. Miss Collins in Southsea again; I wonder why she didn’t try to fit me in before the lecture as she used to!

Saturday 22nd

Slept badly, and cried once or twice, feeling horribly unfit for everything on waking. But having promised to help with the Victoria Nurses Flag Collection I had to go at 9 o’clock. However, I quite enjoyed the amusing experiences connected with this until one o’clock. At 3 o’clock I went to Drayton to Mrs Pink’s At Home to the members of Frech Club - also very enjoyable.

Sunday 23rd

A wakeful night with bad attack of crying at the utter hopelessness of things. Busy in the house during morning. In afternoon I re-read my Cornish diary as a longer interval that that of the two months mentioned by Miss Collins has now elapsed. In the first place I read it through, trying hard to be quite impartial but I could not detect the improvement Miss Collins says is indicated. But with the easily revived memories of the suffering, and the knowledge that I felt no better at the end of the visit it is difficult for me to find what may be called "improvement" in the light of knowledge of analytical technique and a dispassionate state of mind. In the second place I read it through again, giving a "good mark" or a "bad mark" where it seemed possible, with the result that there were 18 bad marks and 17 good marks! After tea I went with Mother to visit friends, practically driven out by my depressed chaotic state of mind.

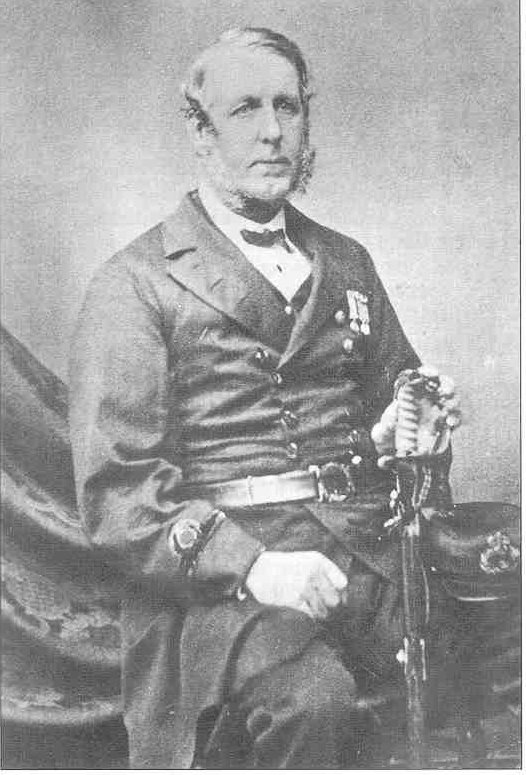

Portrait of my Father

My father was born at Portsmouth in April 1858. His father was then about 40 years of age, and had been a widower when he married my grandmother (age 30) the previous year. I never saw him, as he died before my Father was married. His family had come to Portsea from Frome, Somerset, about 1814, before he was born. They were cloth merchants, and judging from what I have heard I should say they were good yeoman stock, or even an impoverished branch of a county family, for my grandfather was remarkably handsome, six feet in height, with fine golden hair, blue eyes, a sensitive mouth and a delicately chiselled nose – "like a Greek patriarch", as I have heard my Father describe him. Two of his sisters were, I believe, known as "the two beautiful Miss L---s" early in the nineteenth century.

This is a picture of her grandfather

My grandfather seems to have inherited the qualities and tastes that one associates with families which have had the advantages of education and culture for some generations- a fine integrity, family affection and love of home life, and a keen sense of beauty shown particularly in musical ability, appreciation of poetry and love of nature.

As far as I can understand my great-grandfather seems to have acquired the habit of drink; his business diminished in consequence, and he died when my grandfather was eleven years of age. One of the youngest in a family of twelve, it is obvious that he can have enjoyed few educational facilities, and he had to start life early in the Royal Navy under the incredibly hard "lower-deck" conditions of those days. He retired as a commissioned warrant officer (having seen active service in the Crimea, Baltic, etc), and seems to have won great respect, for some of his commanding officers visited him in later years and I have found photographs which I take it they presented to him.

So much for my Father’s paternal antecedents.

His Mother also came from a good West Country family, the E---s, but she had hard conditions and few advantages, for her father , too, was given to alcoholism. She was a woman of strong upright character, rather matter-of-fact and unimaginative, in contrast to the idealistic beauty-loving qualities of her husband.

My father was the first child of their marriage. My grandfather was away some time before and after his birth, and during this time my grandmother was extremely lonely in Portsmouth, having lived all her life in Devonshire and Cornwall, and tradition has it that she found much consolation in love for her cat, which often lay on her shoulders, and this was said to account for my Father’s marked predilection for cats.

It seems to me that early environment influenced my Father’s character in at least two ways. In the first place his father was away at sea for two or three years after he was born, so that he lost the paternal love that otherwise would have been lavished on him; as soon as the child’s character began to show itself, it clashed with that of the father, and so mutual affection was never really established between them. In the second place, the age of the parents, and the remarkably strong thriftiness of my grandmother (it is perhaps noteworthy as showing the austerity of her life that her first visit to a theatre was at the age of 60, when she took me to a pantomime) in particular led them to save in every possible way so that they might buy a house and provide better material advantages for their children than they had enjoyed. Praiseworthy motives in themselves, but doing more harm than good when as a result pocket money, amusements and social opportunities are kept from a child, and his whole life remains tinged with dissatisfaction.

Five years after my Father’s birth a little sister arrived, blessed with a sunny lovable disposition who was naturally much beloved by her father, and other children followed in quick succession, only two of whom survived, but all seem to have been more peaceable and affectionate than my Father who was so full of ill-directed energy that he was always perpetrating boyish pranks which made his parents angry, as they seemed unable to understand the boy’s nature.

According to his own statements in later years he was sent to Greenwich Naval School from motives of economy, and judging from his memories that environment seems to have grated upon the refinement in his character, which was curiously interwoven with a personal disregard for conventions and a liking for the "simple life" crudities of log hut or gypsy tent.

There is a faint family tradition that his parents would have liked him to become a doctor and would, I feel sure, have made any sacrifice to attain this ambition, but he would have none of it – fortunately, to my mind, as he was obviously not suited for such a vocation. As it happened, he insisted upon going to sea, and began his first voyage from Liverpool when 16 years of age, as, I presume, an apprentice on a sailing ship. Except for short intervals the next five or six years were spent at sea or in foreign ports, and I am always glad that he had this wonderful experience, as it is difficult to imagine his life without some spice of true adventure, and some contact with the strong vital things of the earth as distinct from the almost parochial monotony of life as it is lived in a highly civilized country.

It has always been a matter of regret to me that there is no account of his life at sea. He was an excellent raconteur, and the ideal way would have been to take it down in shorthand from his lips, as his own style in writing was sometimes a little stilted. When by chance he had got well started on the subject with friends I would contrive to get hold of a scrap of paper and a pencil and try, unperceived, to jot down his rain of words, but these occasions were rare, and the results cannot be pieced into a whole.

His experience included at least two voyages round the world; he visited India and from there his ship took the first lot of coolies to the Fiji Islands; it was not a pleasant trip as smallpox broke out amongst the crowded natives. On another voyage, I believe, the cargo was wrongly packed, and it shifted in the hold, so that the ship was in imminent danger of capsizing in mid-ocean; a terrible experience for all hands, working day and night to right the vessel.

His ship fought its cold dreary way round cruel Cape Horn, probably more than once, and he was never tired of telling of the beauty of the snowy albatross in its native haunt in that region. Once he deserted his own ship, and enlisted in the Peruvian Navy, and about this time he had a bad attack of dysentery and was in a hospital amongst patients of almost every nationality under the sun, tended by French sisters of mercy. He was stranded on the Pacific coast of the Isthmus of Panama, and did not posssess £5 for the railway journey across, so he walked to the other side, following the railway lines, a distance of about 60 miles though as the crow flies it is only about 20 miles. This meant sleeping on the road for two or three nights, with the virgin tropical forest on either side, which would remain silent during the heat of the day, but would burst forth with the strangest noises at sunset. The crossing accomplished, he sought the aid of the British Consul, and was thus able to work his way home on a liner. The story goes that he arrived in Southsea early one morning, so disreputable a figure in non-descript rags that he could not approach the front door, and crept in to the back of the house to encounter his mother in the kitchen, with what mingled feelings on either side we can only guess at.

After this he was in a hosiery warehouse in London near Cheapside for a short time, and there are traditions of his high spirits here; he was particularly fond of telling us about a bad fire which occurred in a neighbouring warehouse, and how he climbed into the smouldering building over tottering masonry, eluding the watch of the firemen left on guard, and returning to his own quarters with trophies in the shape of silk handkerchiefs, etc.

I don’t know exactly how it came about, but he was soon at sea again, and the next mile-stone I can trace is his entry into the Customs by examination on the 9th December 1880 at the age of 22. I have often heard him relate that he could see no settled future connected with the precarious sea-life, and he therefore decided that he would go in for something which would be a certainty, with a pension attached. On his last voyage he accordingly worked at an old arithmetic and any other books he could get hold of.

He started his new career at Weymouth in a very lowly position, technically known as "outdoor officer, second class", and was transferred about six months later to Portsmouth where he lived with his mother and sister.

During the next three years he seems to have had many interests; he went fossil gathering; he gave lectures on astronomy, making his own charts and owning a magic lantern. He joined the ranks of the "free thinkers" and was an adherent of Charles Bradlaugh in his struggles for liberty of thought - the latter, I am sure, pained his Mother who was a woman of simple faith and piety, tinged with sufficient sense of policy to feel that it was better in many ways to follow the accepted path - a rather typical Victorian attitude, I should say.

From little things I have heard, aided by my imagination, I have an idea that he met several girls who attracted him merely as women who probably made it clear they did not care for him, or thought his position and prospects not good enough. At the same time he was in the difficult position of wanting an intellectual mate whom he was scarcely likely to meet in the small circle open to him. The mating instinct having been aroused, and the home conditions not being very congenial, he was probably led to think of marriage, and he was attracted by my Mother’s housewifely attainments, refined manner, unusual type of features, strong character and intellectual possibilities. To be brutally frank, I feel it was not a perfect match; it lacked the high spirits and abandon that come to two young people who are able to give free expression to their love. And although it might have developed into a very happy marriage, the many limitations due to early environment on both sides, and the extreme thrift necessary to live on a pound a week in two rooms stifled many vital potentialities on either side.

I have referred to my Mother's "strong character", and rightly so, but unfortunately it showed itself in a negative, "peace-at-any-price", rather than in a positive fashion, as a result of a very unhappy childhood and adolescence; the loss of her mother when she was only eleven years of age, and the subsequent marriage of her father with an impossibly vulgar cook accounted for much that would otherwise seem strange.

I was born within ten months of their marriage, and for the first few years I believe I was a great joy to my Father, but I suppose he gradually became more neurotic as the monotony of his work grew upon him, and we seemed to drift apart.

Taking a swift view of his subsequent life, it reminds me of that of a caged wild animal; he wanted wide spaces, simple natural pleasures; adventures and a spice of danger. He was doomed to a round of official work that held little interest. He was always asking for transfers, and had not the "savoir faire" to be tactful with the right people, so that things often went "agley" [ugly].

For instance, he was promoted to King's Lynn in February 1892, didn't like it, and was transferred to London "at his own request" in May. A year later he was sent to Newhaven (Sussex) "at his own request", and there he spent four comparatively happy years, with the nearest approach to a hobby that I can remember – fishing. In 1897 he was again transferred "at his own request" to Belfast, another failure, for within a year he exchanged with an officer at London. Within three years another restless fit came on and he went to Folkestone "at his own request", but only stayed a few weeks owing to insomnia and nervous breakdown. Finally, in 1904 he returned to Portsmouth, an appointment which was only gained by the sacrifice of the rank and pay of first class examining officer for which he had just qualified by examination. Here he finished his official career, retiring about 1919, and this space of 15 years was moderately happy, as the conditions of work were very favourable, things were much easier financially, and he was able to garner many little pleasures from his garden, the sea, and the Hampshire country with which he had been familiar from early boyhood.

I find I have omitted to mention the birth of my brother in London in 1899, the upbringing and companionship of whom provided him with new interests. He was about 5 years of age when the move to Portsmouth took place, and he will probably have many happy memories of country rambles with his Father during the impressionable years of his childhood.

My Father had always been so strong physically and able to do the most rash and unreasonable things without apparent injury that it came as a surprise to everyone in the spring of 1922 to find that he had contracted pulmonary tuberculosis. Everything possible was done for him, but he wasted rapidly, and within 4 months passed away painlessly at the age of 64. He was indeed anxious to go, as he realized only too well that a life without physical health would deprive him of the few pleasures he could enjoy.

In 1914 just before the war he had bought a piece of land in the country and built a little house there, his ideal being that we should all live there. He did not realize that it would have been an unsuitable life for my Mother or myself, and also did not sufficiently understand himself to foresee the many difficulties and disappointments he would have had if we had given up our Southsea home altogether and gone into the country to live. However, I think he gained as much pleasure from this house and land as was possible with such a peculiar temperament.

This brings me to the subject of his character, which is so involved that it almost baffles adequate description. He was born with a wonderful physical constitution, a vivid personality and strong emotions; but the constitution was undoubtedly hindered by weak nerves inherited from two alcoholic grandparents, which probably accentuated the tendency to valetudinarianism which harried him throughout life so that he made himself ridiculous in the eyes of those around him. The emotions and personality seem to have been hampered by inhibitions during infancy and childhood, as already mentioned, so that nothing was able to gain true expression. Instead of a steady outflow of the vital forces they were always meeting with barriers, remaining dammed up for periods until they overflowed and burst forth in strange manifestations which seemed inexplicable to the onlooker. Probably this accounts for the restlessness which always troubled him, driving him at intervals to make sudden decisions which appeared to others so unreasonable and inconsistent. It also seems to explain the sentimental emotionalism which was so marked. There was not that steady flow of love and understanding which can be summed up in the word "lovingkindness", towards others. Indeed, everything seemed to be so bound up with "self" that it was impossible for him to realize the point of view of other people; there was very little tolerance, with the result that he had no friends, for at some time or other he was sure to come against some opinion that clashed with his own.

Another obstacle to social life was the strange interweaving of refinement and crudity. Few people are discerning enough to understand a man who, without training, can appreciate with innate taste the best in literature and art, dress and speech and other forms of expression, and yet have so little sense of the fitness of things that he would cheerfully ignore many of the accepted conventions of civilized life, the necessity for some of which he seemed utterly unable to appreciate. There were a few people who could partly read this riddle, as will be seen from the following extracts from letters of sympathy received at the time of his death. The first is from Dr Morgan, a cultured, highly bred man who can follow conventions without being a slave to them.

"I personally had always a great respect for Mr L. and admired his keen perception of the falsity and sham of modern life. Unfortunately one cannot swim against the stream. No amount of caging could tame Mr L.’s bold spirit, but alas in this world one is drowned in a fearful ocean of unreality. I myself feel that I have lost a dear old friend, one whom one will not easily forget."

And this one is from a girl friend of mine: "In a sense it was a happy ending for your father, for he always seemed to be out of joint with the world; not surprising, with the world as it is! But I shall always remember the happy glimpses one got of his truly poetic soul. I expect your own aptitude to appreciate and be able to express beauty derives from him."

It is not surprising, perhaps, that extreme pessimism should be the outcome in a personality so badly equipped to face life as it is. For this world he could see no prospect but repeated wars, over-population and ever-increasing estrangement of man from the beauty and vastness of Nature. And as regards a future life his keen intellect refused to accept any arguments in favour of the survival of personality after death, and yet there was a lurking desire for such a faith. I think the quotation of some of his favourite passages will throw more light on this side of his character than I could hope to do.

"From too much love of living,

From hope and fear set free,

We thank with brief thanksgiving

Whatever gods may be,

That no man lives for ever

That dead men rise up never

That even the weariest river

Winds somewhere safe to sea."

(Swinburne)

"When I am dead, my dearest,

Sing no sad songs for me;

Plant then no roses by my head,

Nor shady cypress tree;

Be the green grass above me

With showers and dewdrops wet;

And if thou wilt remember

And if thou wilt, forget.

I shall not see the shadows,

I shall not feel the rain;

I shall not hear the nightingale

Sing on as if in pain;

And, dreaming through the twilight

That does not rise nor set,

Haply I may remember,

And haply may forget.

(Christine Rossetti)

Unfathomable Sea, whose waves are years!

Ocean of Time, whose waters of deep woe

Are brackish with the salt of human tears!

Thou shoreless flood, that in thy ebb and flow

Claspest the limits of mortality,

And, sick with prey, yet howling on for more,

Vomitest thy wrecks on its inhospitable shore!

Treacherous in calm, terrible in storm,

Who shall put forth on thee,

Unfathomable Sea!

(Shelley?)

In conclusion I would venture the opinion that my Father’s was a character full of the most wonderful potentialities, and judged by that standard his was indeed a wasted and unhappy life. Probably that can be said of most people, but it was exceptionally marked in this case. Yet although he never had average balanced happiness, it must be admitted that he was able to lose himself in his own particular pleasures connected with life in the open, so that he had that advantage over the neurotic who can never or seldom get any real feeling of enjoyment.

The truth of this can, I think, be seen from the two first letters attached. The last letter, dated 1898, is a pathetic memorial to one who was tortured with flashes of insight, but was too heavily shackled to allow the sentiments to come to fruition in action. It was written when I was twelve years of age, and I fear it had as little effect as is usual with exhortations from those who are unable to be a living example of what they urge.

3/8/06

"My dear Rosalind,

Your welcome letter of yesterday has just come. I have been pottering in the garden, enjoying the cool and almost stormy breeze which one can appreciate after the intensely warm weather which has prevailed for so long. I can imagine what it has been like in that vast wilderness of brick, slate and stone called London. It has been sufficiently trying here where there are always currents of pure air on the move. I have often thought of you working hard in the city and travelling in oven-like railway carriages, and wished that your conditions of life were more wholesome.

I cannot adequately describe the summer weather we have had down here. Considered simply as summer weather it has been magnificent and perfect. Lovely breezes, Italian skies, beautiful feathery clouds, deliciously cool evenings, nights and early mornings, and at least one beneficent spell of cooling refreshing rain for a few hours. Many people sing praises and dwell with enthusiasm on holidays under such conditions, but personally while quite recognizing its perfection as summer weather I cannot enjoy it, and would much prefer to take a holiday in the cooler autumn. I have felt half dead except in the early mornings and the evenings......

During the last week or two the Island has often been a lovely spectacle, marvellously clear and reminding one almost of the Celestial Land beyond the river of Death as described by that rugged genius Bunyan.

You alluded in a recent letter to our garden. Well, it has been a dream of delight, a poem in colours. The Shirley poppies have been lovely, of every tint from snowy white to darkest crimson, and of every degree of mixture of those colours. There have been literally hundreds of them; every morning has disclosed a fresh bevy of them. My first action on rising is to go out into the garden and pick a large bunch for the table.

Bees of many sorts filled the air with their deep notes as they plunged into the glowing cups of the beautiful flowers, emerging as dusty as millers with the fertilizing pollen and so acting as agents of communication between the passionless plants.

We have had as many peas as we could possibly eat and now the plants are all out of the ground and nearly all consumed in the purifying and pest destroying refuse-fire. The scarlet runners are now yielding fruit and there are carrots sufficient for many meals. The sweet peas have been quite done for by the aphides or green flies of which there have been almost thousands. The yews and other trees and plants are doing well and the ferns in the greenhouse, etc, also.....

If the weather is favourable I intend having a night "sub Jove" on Saturday or Sunday. A night alone under the stars has a refining and soothing influence which can be better felt than described. To watch the sun disappear, the shadows darken and the stars, "bright legions on the sapphire plains", gleam out, and to feel absolutely alone with nature and free from the artificial trammels of civilized existence is food for the soul and is an act of worship to the unknown Deity which far transcends any that can be experienced within walls.

If I can realize my desire I will give you the narrative in my next letter..."

15.8.04

"My dear Rosalind,

Where do you think I had breakfast, and with whom, yesterday (Sunday) morning? As you would guess I will tell you. I had my breakfast on St Helens village green. St Helens, Isle of Wight, in the company and as the guest of a travelling showman and his family, in the midst of their domestic caravans, four of which were ranged in line. In front of the patriarch’s caravan there sat a clean and wholesome and ruddy-faced group at an improvised table on various substitutes for chairs. They were having breakfast of bread and butter and tea, and I, arriving on the scene from Brading Harbour after a night under a farm wagon and the stars, shooting and otherwise, felt as if something hot was just what I wanted, passed close by the group. The patriarchal "boss of the show" greeted me kindly with a remark on the strong wind, and I in responding asked if I could be obliged with a cup of tea. I received a cordial assent, and flinging down my haversack, and brown blanket, sat upon the grass close to the homely wife of the patriarch. I was soon munching bread and butter and enjoying a really good cup of tea. There was also a daughter of the patriarch who was not only homely but comely, and as Pepys would say "did take my eye mightily", and many a sly glance did I take at her the while I sipped the grateful and comforting tea. In front of us were the steam-galloping horses, and further off boatswings, a coconut range, a shooting range at which the marks were glass bottles, many necks of bottles still dangling in the gale while the fragments lay in a heap beneath, other catchpenny contrivances there also were which were not so familiar to me. Four asses and several cows walked slowly around and about, and a watchful and snarling dog was tethered to the wheel of the patriarch’s caravan. The two other vans were the dulce domums of the sons-in-law of the patriarch and their wives and families, the children ranging from 10 years to 10 months, and infantile music was vouchsafed to us at intervals. The sunshine was glorious and the wind boisterous, and I relished my meal greatly. I spent three hours altogether talking to the old man who was as shrewd as kind, and had original opinions on all subjects. He knew Lynn and its "mart" on the 14th February every year very well. In the first place he had been on a farm in Northamptonshire in his youth, and eventually drifted into the showman’s business. He informed me that he was now retiring and wanted a purchaser for his show either as a "going concern" or piece-meal. He had had various gentlefolk to see his living vans with a view to buying one, there being a craze he informed me for gentlefolk to live in such during the summer. Altogether I had a novel and pleasant experience with these folk. The patriarch would not hear of payment for my meal, so I bestowed some coppers on a sturdy grandson of his of about 10 years.

On the Saturday, the weather being just right I thought I would get free for a time from the galling and wearisome bonds of conventionality, so I commandeered a brown blanket, and with some provender, a book of verse (Omar), but neither flask of wine nor thou, took the 6pm boat for Sea View and walked to St Helens. From the latter place a semicircular road, on a made embankment divides the tidal harbour of Bembridge from the old harbour of Brading, and was built a few years ago to reclaim the latter, which is now converted into marshy grazing lands intersected by watercourses. The shades of eve were falling fast when I got to this road and I abandoned my intention of going over to the Bembridge side and doing a lot of trespassing and creeping through small apertures in cunningly constrived barbed wire obstructions, and turned my attention to the marshy lands between the road and Brading. Here I found an ideal "pitch" for sleeping out in the form of a small hayrick with a farm cart backed up against it and a canvas covering over all. There I laid me down in peace to sleep and watched the lovely stars and munched my frugal supper and pitied "Sultan Mahmud on his throne". I had a luxurious couch of the fragrant hay and slept fairly well. At 5 in the morning I woke and found a strong wind from the South West making music in the distant trees. I had a mouthful of "vittles" and returned to my blanket till 8 when I packed up and returned to St Helens with the result already described.

After leaving the showman I went down to Bembridge wharf to fish, but the wind was by then a gale, and the dust from the afore-mentioned road was blinding and suddenly with but little warning it began to rain furiously. Accordingly I made all snug for heavy weather which consisted in donning my veteran Snowdon cape, and started to walk to Ryde (about 4 miles) as I feared the Sunday launch to Sea View would be stopped by the gale. For some time it rained in sheets driven violently by the gale, and I got what little shelter I could as I walked from the high hedges. And now occurred the funniest incident of all. I was overtaken by a man driving a hooded Victoria, and he accosted me with "do you want a ride?" "How much to Ryde?" I queried. He replied "a shilling". As I was already wet I said "No, I will walk, thanks". He at once reduced his price to "a tanner", to which I agreed, and he drove me to the parade near the Pier. On the way I examined my small change and found I had nothing smaller than a shilling and I anticipated that he would pretend to have no change. Sure enough when I gave him the shilling he couldn’t find a sixpence to give me but he had three pence. Now I am very slow-witted in giving change but I thought I had hit upon a plan; so I asked my John "Have you a half-crown?" Yes – he had. "Well," said I, "if I give you another shilling and you give me a half-crown that’ll be right." He looked solemn and perplexed, and I said testily "Come along now, I shall lose my passage to Southsea." So I handed him another shilling and he gave me the half-crown. I hurried down the long pier to get the steamer, and it did not dawn upon me that John had paid me sixpence for the privilege of driving me into Ryde until I got to Sussex House. If that man ever discovers the true inwardness of that transaction he will be as stupefied as I was and the air will go blue with appeals unto strange gods."

?1898

"My dear Rosie,

I was very pleased to receive your letter and was proud and delighted to learn that you had won a gold watch. I shall be quite eager to see it. You must be very careful of it, both as to how you treat it, and as to when and where you wear it so as not to run the risk of losing it or having it stolen. You must be particular to wind it up regularly every night. I was glad to hear that you had a day over the Hill with Johnnie and Uncle Alfred, also that you had been on the Pier to hear the Bands. You must have had a pleasant evening at Mrs Malpas’ house.

I hope you will win something in the "Portsmouth Times" competition, although you can afford to be content with not doing so after your great success in the Sunlight competition.

I hope, my dear, that you are well and happy and that you will ever strive to be helpful and considerate to those around you. By so doing you will make both yourself and others happy. But if you give way to selfishness you will never be truly happy or contented. I know this from my own experience. I want you to write to me once a week, and you will find it a good plan to select a particular day of the week upon which to do so. It will cheer me up, and benefit me, to receive a letter from you regularly and if you should have any difficulty to contend with or any question to ask me, do not hesitate to open your mind to me because I am your father, you know (although not such a good one as I should like to be) and I am therefore your natural protector, as also your mother is. Let us therefore do all we can to help and encourage one another while we can.

The weather has not been so favourable since I left Portsmouth as it was previously. We have had it both wet and cold. Yesterday and today have been finer and warmer. All here send their love. For the present I will conclude with my very best love and remain

Your loving Father.

P.S. Do not neglect to practise all the pieces you know, and the exercises on the piano. It would be very foolish for you to neglect your music."

This is a picture of her father and mother